An On-the-Ground Look at the Greater Bay Area Retirement Wave

——Experts: Emotional Needs Cannot Be Outsourced; A Parallel Hong Kong–Mainland Approach Is Optimal

With the reopening of the border between Hong Kong and the Mainland, Hong Kong residents have flocked northwards. The phrase “good value for money” has become the golden incentive behind all cross-border activities, and “Greater Bay Area retirement” has also become a hot topic. However, having overly high expectations may not be realistic. Blue skies, fresh air, and birdsong in the Mainland may not necessarily compensate for elderly people’s emotional attachment to familiar communities. Experts share that the Greater Bay Area should be viewed as an independent retirement option, while current efforts should focus on strengthening community care, so that the majority of Hong Kong’s elderly can enjoy their later years in peace.

“We now regularly organise visits for Hong Kong residents to come over, stay for a few days, experience it firsthand, and let them vote with their feet!”Mr. Li, a sales manager of a national high-end elderly care group, spoke with great confidence about the conditions at the retirement complex. Recently, he has received many Hong Kong retirees or soon-to-retire individuals.

On the day of the interview, the reporter was picked up by Mr. Li and driven eastward from the Liantang Control Point. After a 50-minute journey, they arrived at a retirement complex located in a suburban area of Shenzhen’s Dapeng New District. At the same time, a Hong Kong visitor group also arrived. The elderly visitors took the opportunity to check in and take photos in the bright and polished lobby.

The complex operates under a unified national model and adopts a new form of elderly care, offering independent residential units that can accommodate up to 1,200 elderly residents. According to Mr. Li, the recreational facilities are comprehensive, and the complex is also equipped with a rehabilitation hospital. Elderly residents suffering from chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes can attend follow-up consultations and collect medication on site. The facility is also capable of handling certain levels of acute and critical medical conditions.

A Booming Elderly Care Industry

Ms. Yip, a Hong Kong resident in her eighties, is a retired mechanical and electrical engineer who has been divorced for many years. Before moving to Dapeng Bay for retirement, she lived alone in a rented flat in Mei Foo Sun Chuen, paying a monthly rent of HKD 18,000. Her married eldest son would occasionally come by to cook for her. She recalled, “Since September this year, my appetite declined. Sometimes I only ate one bun a day. Recently, there was major renovation work right across from my flat, which triggered my asthma. I couldn’t catch my breath and had to call an ambulance in the middle of the night to go to the emergency department.” At the time, her lease was about to expire and she was looking for a new place to live. Through a friend’s introduction, she came here for a trial stay accompanied by her eldest son. She found the experience satisfactory and decided to move into a one-bedroom unit. She said with a smile that the three daily meals here are very generous, and her appetite has clearly improved. The staff and fellow residents are very friendly, and she added that even during asthma attacks, she can receive treatment at the on-site hospital.

Mr. Li and other Mainland industry players setting their sights on Hong Kong’s elderly care demand is hardly surprising. On one hand, elderly care institutions on the Mainland are facing “overcapacity.” Across Guangdong Province, there are 1,638 elderly care institutions providing a total of 213,000 beds. Of these, Shenzhen alone accounts for 14,000 beds. Mainland experts estimate that the overall occupancy rate is only slightly above 40%.

▲ In recent years, the trend of retiring northward has gained momentum. Helping Hand has also organised short-stay trial experiences for elderly participants at its Zhaoqing care home. On the day of the reporter’s visit, a pickleball activity was being held at the facility.。 (Photo taken by Lee Chun Kit)

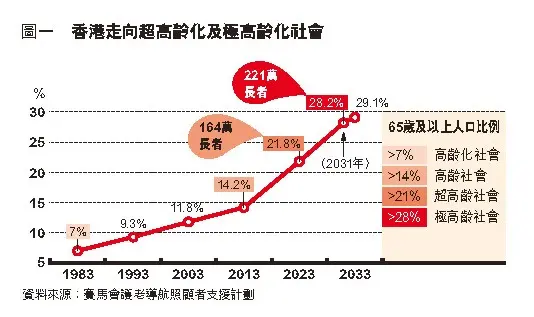

On the other hand, demand for elderly care in Hong Kong remains strong. Hong Kong has already entered a “super-aged society.” At present, nearly 1.64 million people are aged 65 or above, accounting for 21.8% of the total population (Figure 1). This proportion is expected to rise to one-third by 2046, pushing Hong Kong into a “hyper-aged society” and making it one of the most rapidly ageing cities in the world. Elderly care has gradually become a shared social concern in Hong Kong.

“After just two years of operation, more than 600 residents have already moved in, around 10% of whom are Hong Kong residents,” Mr. Li noted. Most Hong Kong residents choose the more affordable “small one-bedroom” self-care units, with a floor area of approximately 31 square metres. Monthly room charges are slightly over RMB 8,000, and inclusive of meals, total monthly expenses amount to around RMB 10,000. Mr. Li believes that high-end elderly care services on the Mainland are particularly attractive to Hong Kong elderly who are “not wealthy but relatively financially secure.” He expects that more Hong Kong residents will choose to move in with minimal preparation in the future.

It is not only the Mainland elderly care industry that welcomes Hong Kong seniors retiring in the Greater Bay Area. In recent years, the Hong Kong Government, which has been grappling with fiscal deficits, has also become an active proponent.A review of information from the Social Welfare Department (SWD) cited in the Budget shows that in 2023/24, the average monthly cost per subsidised residential care place ranged from HKD 16,413 to HKD 23,128. If such services are outsourced to the Mainland, the average cost can be reduced by as much as three-quarters, to approximately RMB 4,000 per month.

Outsourcing Elderly Care

The Social Welfare Department launched the “Guangdong Residential Care Services Scheme” (the “Scheme”) in June 2014. Over the following decade, only two care homes joined the Scheme, allowing eligible elderly persons on the Central Waiting List to be fully subsidised by the Government for residential care. Between May 2024 and November 2025, however, the SWD successively added 22 elderly care homes in the Greater Bay Area to the Scheme, covering eight other GBA cities outside Dongguan. Among them, Guangzhou (7 homes), Foshan (6 homes), and Shenzhen (5 homes) account for the majority.

Last month, the reporter visited one of the Scheme’s two original participating institutions — the Hong Kong Jockey Club Helping Hand Zhaoqing Care and Attention Home for the Elderly. Located in a suburban area of Zhaoqing and surrounded by hills and forests, the facility offers expansive views of blue skies and a tranquil environment. Covering an area of 40,000 square metres, equivalent to six standard football pitches, the home features vegetable gardens, walking trails, and even livestock sheds, providing residents with a leisurely and pastoral lifestyle.

▲ Zeng Zi-yang (far left) engaging with elderly residents who travelled from Hong Kong in the courtyard garden.

Ms. Lo, who suffers from hypertension and other chronic illnesses, originally lived with her son’s family in Jordan. However, her son worked long hours and faced significant financial pressure, making it difficult to hire a domestic helper whose wages continued to rise. “The salary went up from just over HKD 4,000 to later quotes of HKD 6,000 or even HKD 7,000. How could we afford that?” she said. She also recalled having fallen at a wet market and hitting her head. Her family became worried about leaving her alone at home, fearing she might go out by herself and suffer another accident. Moreover, she felt that the environment in Hong Kong’s elderly homes was generally poor. After discussion, the family decided that she should move into the Zhaoqing care home.

▲ Ms. Lo, who has lived in the care home for over a year, recently learned to play the tabletop game Rummikub.

“Here, I wake up at 5:30 every morning, practise Baduanjin, have breakfast, and then play mahjong. Lunch is at 11:30, followed by a walk and an afternoon nap until 2:30. In the afternoon, there are activities again.” Ms. Lo described her daily routine to the reporter step by step, laughing as she shared that she had recently learned to play Rummikub, often referred to as “Israeli mahjong.” “It’s quite fun.”

When asked whether residents also farmed, she laughed: “No, it’s the staff who plant the vegetables. We elderly residents help with harvesting. I’ve picked longans, lychees, and tomatoes myself. Life here has been very relaxed over the past year or so. I weigh myself every morning — I’ve even gained a little weight recently!” Ms. Lo appeared very satisfied. She currently shares a four-bed room with another elderly resident, and the wall beside her bed is covered with warm family photographs.

Ms. Connie Chu, Director of Operations at Helping Hand, who has spent many years managing elderly care institutions, observed that the current wave of northbound retirement differs from earlier trends in which Hong Kong retirees purchased homes in places such as Zhangmutou or rural areas. The key difference, she explained, is the increased understanding of and confidence in Mainland healthcare services. “During the COVID-19 pandemic, the entire city was locked down. Returning to Hong Kong for specialist follow-ups, collecting medication, or even having medicines delivered across the border was simply not possible.”

▲ “Even now that the border has reopened, fewer people feel the need to return to Hong Kong for follow-up consultations,” Ms. Chu added.

As a result, Hong Kong elderly residents began receiving generic medications for conditions such as hypertension and diabetes at local hospitals. After taking them, many found the treatment acceptable. Based on two to three years of data from the care home, she noted that only in cases where elderly residents require scheduled surgical procedures do they return to Hong Kong. Otherwise, treatment is generally handled locally. “Even pain relief medications for cancer patients are prescribed locally,” she said.

Mr. Zeng Zi-yang, Director of the Zhaoqing home, supplemented that after Hong Kong elderly residents have lived in Mainland care homes for six months, the institution assists them in applying for a residence permit. With this permit, they can pay RMB 400 per year to enrol in the Basic Medical Insurance for Urban and Rural Residents, which covers part of their inpatient and outpatient medical expenses, with a reimbursement rate of approximately 65%. In addition, elderly residents can now use HKD 2,000 worth of medical vouchers locally, which further helps to ease part of the medical expense burden.

As at mid-2024, the number of Hong Kong residents aged 65 or above who had settled in Guangdong Province (Greater Bay Area) reached 100,000, accounting for approximately 6% of Hong Kong’s elderly population — an increase of over 40% compared to ten years ago. Hong Kong’s residential care home placement rate stands at 4.1%, the highest in Asia (Table 1). Following the recent surge in northbound retirement, the Guangdong Residential Care Services Scheme has also gained popularity. Since May 2024, the cumulative number of elderly residents admitted under the Scheme has reached 624, roughly equivalent to the total number recorded over the Scheme’s first ten-plus years (Table 2).

Nevertheless, even if the potential beneficiary base were to double in the future, the Central Waiting List would still have as many as 17,600 applicants (Table 3). At present, the Scheme only offers limited relief. Relying entirely on the Greater Bay Area to resolve Hong Kong’s elderly care challenges is unrealistic. Ms. Connie Chu, Director of Operations of Helping Hand, also pointed out that even Mainland China’s elderly care policy advocates the “9073 model” — namely, 90% of elderly people ageing at home, 7% relying on community-based care, and only 3% living in residential care institutions.

She believes that residential care homes should primarily serve elderly people who face genuine difficulties in care, such as those who are physically frail, have complex medical conditions, or exhibit behavioural issues. These cases are often difficult for families to manage, and home-based support services may also be impractical. “Residential care services should move towards greater professionalisation,” she said.

For other cases, efforts should focus on supporting elderly individuals to remain in their own homes for as long as possible.

Weighing the pros and cons, Mr. Wong Cheuk-kin, founder of Elderly Home, Hong Kong’s largest professional elderly care consultancy platform, suggested that the Government could consider allowing private institutions to establish specialised residential care homes in the Mainland for persons with intellectual disabilities, psychiatric patients, or elderly people with dementia, while allowing residents to continue receiving government welfare support.

Addressing the first two groups, Mr. Wong highlighted a harsh reality: “Family visitation rates are very low. From my observations, out of ten residents, only two or three receive visits from family members. Even when visits do occur, they may happen only once every year or year and a half.” He described these as “hands-off cases”, where family members have largely withdrawn from caregiving responsibilities. Such cases typically require relatively few follow-up medical appointments and are therefore more suitable for services in the Greater Bay Area.

As for dementia care, Mr. Wong noted that Hong Kong currently has only one specialised facility — the Jockey Club Centre for Positive Ageing. “By using Hong Kong funding to hire staff in the Mainland, we could significantly increase caregiver-to-resident ratios for elderly people with dementia,” he said.

▲ The field of rehabilitation and professional medical care in Hong Kong has accumulated rich experience. The picture shows the Hong Kong residence of the Helping Hand. (Helping Hand official website)

The “Hong Kong Elderly Care Model” Moves North

For many years, the “Hong Kong model” has been an example for the Mainland to learn from — whether in financial reform, land-based public finance, or wage protection schemes. This time, it is elderly care that is being exported.

Ms. Connie Chu, Director of Operations of Helping Hand, explained: “Hong Kong’s rehabilitation services are relatively well developed, and our allied health services are also more mature.” Using physiotherapy and occupational therapy as examples, she noted that on the Mainland, distinctions between these disciplines are often blurred and collectively referred to as “physical therapy,” despite their importance to elderly care.

She explained that when elderly people lose physical functions due to illness or degeneration, physiotherapists assess how much muscle strength can realistically be restored and then design appropriate training programmes. However, improvement has its limits — just as it is unrealistic to expect a stroke patient to run. Occupational therapy, by contrast, focuses on helping elderly people live their daily lives using their existing physical abilities. For example, after a stroke that paralyses one side of the body, occupational therapists help patients maximise their remaining abilities to maintain quality of life within those limitations.

Helping the Elderly Make the Most of Their Abilities

“We strongly encourage elderly residents to live using their own abilities,” Ms. Chu emphasised. “Otherwise, the ‘sick role’ becomes too dominant. Their condition deteriorates, they stop moving, and eventually even their remaining abilities are lost.” She further clarified that physiotherapy and occupational therapy are fundamentally different concepts. “In Hong Kong, services are provided based on this professional distinction. What people refer to as ‘Hong Kong-style care’ is precisely the use of professional assessment combined with attention to the elderly person’s psychological needs.”

She added that Helping Hand arranges weekly visits by Hong Kong staff to Zhaoqing to provide professional training to local staff, covering areas such as end-of-life care, bereavement counselling, and physiotherapy. The operational model of the Zhaoqing home has absorbed many elements of Hong Kong’s approach. “Care for the body, mind, social life, and spirituality is not simply about having activities to play or meals to eat,” she said.